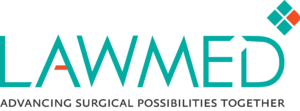

Parastomal hernias are the most common complications after ostomy formation,1 occurring when the edges of a stoma come away from the muscle, allowing abdominal contents, usually a section of the bowel, to bulge out.

Not only can this cause the stoma to leak, but it can also causes pain for the patient.

Parastomal hernias and

how to prevent them

It is difficult to give an exact figure for how many patients are diagnosed with parastomal hernias as the way in which they are diagnosed varies, which has resulted in inconsistencies in the data surrounding them. When CT scans are employed, recorded incidences can exceed 70%.2 Risk seems to increase the longer the stoma is in place, with the incidence rate one year after stoma implementation at 30%, rising to 40% in the second year and 50% by the third year. At twenty years, the rate can reach as high as 76%.2 Another study states that incidences can reach as high as 78%, still developing 20-30 years after the procedure.3

Parastomal hernia

risk factors

Several factors beyond how long the stoma is in place can affect the risk factor for patients. These are:

- Increased BMI

- Older age

- Increased incision size

- Presence of other abdominal wall hernias4

The impact of parastomal hernias

For many patients, parastomal hernias are asymptomatic and can be managed without intrusive measures, but some patients suffer significant morbidity and require emergency hernia repair. The impacts on patients can include pain, stoma leakage and skin excoriation. In more extreme cases, the bowel can be incarcerated, obstructed or strangulated.1

In a study focusing on the impact of parastomal hernias, 139 patients answered a questionnaire after stoma implementation. 79 of these patients had developed parastomal hernias and a linear multivariate regression showed the hernia had caused a decrease in physical functioning (difference -10.2, p = 0.033) and general health (difference -9.0, p = 0.021) as well as an increase in pain (difference -11.3, p = 0.009).5

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic halting elective care, there is an unprecedented backlog of patients awaiting treatment, including patients suffering from parastomal hernias. Due to long waiting lists, patients are having to wait longer for treatment and consequently their conditions worsen, often meaning they end up needing emergency treatment. The impact of this is that the waiting list continues to grow as non-emergency cases are pushed back to prioritise emergency cases, increasing the likelihood of them becoming emergency cases as they wait longer for care.

With such high parastomal hernia occurrence rates and a backlog that continues to grow, it is more important than ever before to be able to prevent parastomal hernias from occurring in the first place.

PREVENTING PARASTOMAL HERNIAS

A 2019 paper stated that the mesh repair technique for parastomal hernias leads to a statistically significant lower incidence rate for recurrence than would be the case without the mesh, wherein the recurrence rate has been shown to be almost nine times higher.2 There are different techniques for mesh repair, but currently, there is no clinical evidence to suggest one method of inserting mesh is more effective than the others.

WHY IS THERE A NEED

FOR LOW IMPACT SURGERY?

PRACTICE OF PROPHYLACTIC MESH

Due to the high rate of parastomal hernias, some surgeons prefer to insert the mesh during the original stoma surgery, before hernias occur. However, there is divided opinion on the efficacy of this.

One meta-analysis looked at whether prophylactic mesh prevents parastomal hernia. In this paper, ten randomised trials that screened 150 studies was compared; in total, 649 patients were included with 324 receiving mesh. In the mesh group, there were 53 parastomal hernia’s (16·4%). Whereas, 119 patients out of 326 (36·6%) in the non-mesh group had a parastomal hernia. The paper concluded, that prophylactic mesh reduced the rate of parastomal hernia repair by 65%(P = 0·02). There were no differences in rates of parastomal infection, stomal stenosis or necrosis. Mesh type and position, and study quality did not have an independent effect on this relationship.6

On the other hand, a second study examined 232 patients undergoing stoma implementation. After 1 year, 211 of 232 patients underwent clinical examination, and 198 underwent radiological assessments.

For patients where mesh had been used, operation time was 36 minutes longer, but there was no difference in the rate of parastomal hernia occurrence found in the clinical (p= 0.866) or radiologic (p= 0.748) data. Likewise, there was no significant difference in the perioperative complications.7

The second study found no clinical difference in using or not using prophylactic mesh, however, this may prevent a second surgery for patients, meaning that further analysis is worth exploring.

THE STAPLED MESH STOMA

REINFORCEMENT TECHNIQUE (SMART)

SMART creates a reinforced stoma trephine using a purpose-designed circular stapling gun of various diameters. The stapling gun creates a precise trephine and simultaneously fixes a mesh sub-peritoneally and circumferentially.8

In a case-controlled pilot study, 22 patients underwent SMART, 18 of which were open surgery and 4 of which were laparoscopic. There were no intra-operative or early stoma complications.

During a median follow-up of 24 months, four patients (19%) were diagnosed with recurrent parastomal herniation, with one patient requiring re-operation. In the control group, the rate of parastomal herniation was 73%.8

Further study is required around the SMART technique; however, initial studies indicate it is both clinically effective and safe. 8

THE SUGARBAKER TECHNIQUE

The Sugarbaker technique occurs after a parastomal hernia is repaired to prevent reoccurrence. The bowel is lateralised and covered with a mesh, allowing a 5 cm overlap.9

In a 2021 retrospective study, 47 patients with parastomal hernias following ileal conduit urinary diversion were operated on. 18 patients underwent keyhole repair, and 10 patients underwent the Sugarbaker technique.

The other 38% underwent various other methods which were excluded from the results. The overall parastomal hernia recurrence rate during follow-up was 18%, with rates of 22% and 10% for keyhole repair and the Sugarbaker technique, respectively.10

PARASTOMAL HERNIATION PREVENTION GUIDELINES

Currently, there are not any guidelines in place to recommend prophylactic mesh use or not, however, new guidelines are to be released at the BHS conference in October.

USE OF DYNAMESH

Dynamesh provides anatomically correct mesh for any mesh insertion, but due to its specialist features, the ISPT can be especially useful in the repair of parastomal hernias.

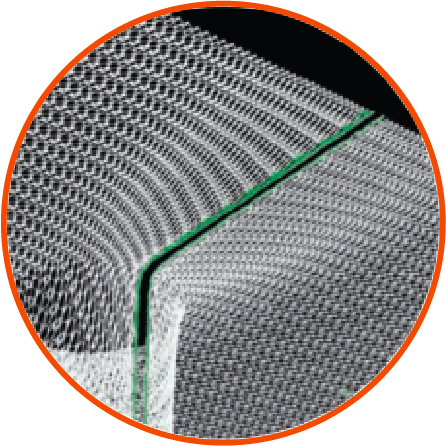

The ISPT implant is made from a single piece of mesh for a seamless junction with the elastic panel. The three-dimensional pre-shaped implant provides excellent elasticity and flexibility to facilitate improved stomaplasty preparation for surgeons.

The dual-layer composite structure promotes rapid ingrowth into the abdominal wall whilst reducing the risks of adhesions on the visceral side.

The elastic funnel is free of sharp selvedges, leading to secure integration of the terminal segment of the bowel and prevention of parastomal herniation.

The ISPT-R can be placed without detaching the stoma from the stoma wall, as the prefabricated slit makes it easier to place the mesh implant around the terminal section of the bowel.

OTHER TYPES OF HERNIAS

In addition to the ISPT meshes for parastomal hernias, Lawmed also offers Dynamesh iPOM meshes. The Danish Hernia Database, with a follow-up of more than 10 years, shows that iPOM has been safe and effective for over 10 years.

References

1. Pianka F, Probst P, Keller AV, et al. Prophylactic mesh placement for the PREvention of paraSTOmal hernias: The PRESTO systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0171548. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0171548

2. Techagumpuch A, Udomsawaengsup S. Update in parastomal hernia. Annals of Laparoscopic and Endoscopic Surgery. 2019;4(0). doi:10.21037/ales.2019.07.06

3. Aquina CT, Iannuzzi JC, Probst CP, et al. Parastomal Hernia: A Growing Problem with New Solutions. DSU. 2014;31(4-5):366-376. doi:10.1159/000369279

4. Sohn YJ, Moon SM, Shin US, Jee SH. Incidence and Risk Factors of Parastomal Hernia. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2012;28(5):241-246. doi:10.3393/jksc.2012.28.5.241

5. van Dijk SM, Timmermans L, Deerenberg EB, et al. Parastomal Hernia: Impact on Quality of Life? World J Surg. 2015;39(10):2595-2601. doi:10.1007/s00268-015-3107-4

6. Meyer J, Delaune V, Abbassi Z, et al. PROphylactic MESH (PROMESH) for stoma closure: does it reduce the incidence of incisional hernia? Protocol for a triple-blinded randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2021;11(12):e053751. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053751

7. Odensten C, Strigård K, Rutegård J, et al. Use of Prophylactic Mesh When Creating a Colostomy Does Not Prevent Parastomal Hernia: A Randomized Controlled Trial-STOMAMESH. Ann Surg. 2019;269(3):427-431. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000002542

8. Williams NS, Hotouras A, Bhan C, Murphy J, Chan CL. A case-controlled pilot study assessing the safety and efficacy of the Stapled Mesh stomA Reinforcement Technique (SMART) in reducing the incidence of parastomal herniation. Hernia. 2015;19(6):949-954. doi:10.1007/s10029-015-1346-9

9. Robotic Parastomal Hernia Repair: Sugarbaker Technique – SAGES Abstract Archives. SAGES. Accessed September 30, 2022. https://www.sages.org/meetings/annual-meeting/abstracts-archive/robotic-parastomal-hernia-repair-sugarbaker-technique/

10. Mäkäräinen-Uhlbäck E, Vironen J, Vaarala M, et al. Keyhole versus Sugarbaker techniques in parastomal hernia repair following ileal conduit urinary diversion: a retrospective nationwide cohort study. BMC Surgery. 2021;21(1):231. doi:10.1186/s12893-021-01228-w